Introduction:

Dr Prasun Kumar Das is currently serving as the Secretary-General of APRACA based in Bangkok where he is leading the Secretariat function of the 76 member institutions spread over 21 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Before this assignment, he completed his term as the Project Manager in implementing IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development) regional project on ‘Rural Finance Best Practices: Documenting and Piloting’.

Dr Das received his PhD in Agricultural Sciences (Agronomy) with specialisation in Post-harvest Management and also held a Master’s in Business Administration (MBA) with specialisation in Financial Management.

The main areas of work and Dr Das are synergising agriculture and farming system with the value chains and access to finance for enhanced productivity and efficiency of the smallholder farmers. He is a recognised leader in the areas of value chain development and finance, agriculture for nutrition and linking farmers with the support systems in South Asia, South-East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa and published more than 20 international papers on the area of his specialisation.

Q) I would like to start this conversation by requesting you to kindly brief our readers about APRACA and the work that it is doing in improving rural credit in the Asia Pacific region.

Prasun Das:

APRACA was established by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) in 1977. The basic idea of this organisation was to have a regional member-based association of financial service providers.

During the 1970s, countries in the Asia Pacific and in other parts of the world were facing a significant challenge of “food security” where there was an ongoing food crisis. All the developmental organisations realised the importance of providing investment and capital for developing agriculture. For that purpose, FAO established three regional associations – one here in Bangkok which is APRACA, one based in Nairobi, Kenya which is called I and one more based in Aman, Jordan which is called NENARACA. Established in 1977, these three associations were the associate agencies of the UN. They aimed to provide an impetus to agricultural finance and to support agricultural development in the regions.

The mandates were mostly regional, but with a global outlook to work with communities. With the start of the new millennium, these regional associations along with two more agencies namely, ALIDE, based in Lima, Peru and CICA based out of Zurich, Switzerland, joined in organising the global community with the introduction of World Congress on Rural and Agricultural Finance which are hosted in different continents.

The 43 years journey of APRACA has been extremely fruitful. If you look at the significant developments across the region in agricultural finance and policy, APRACA drove them through its initiatives. We have received much support from the FAO, along with organizations like The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH), Syria Populate and the World Bank, and several international agricultural research institutes under the CG system, have supported us thus far.

You might be aware that the APRACA membership ranges from the government agencies, line departments specifically the agricultural departments, central banks, national development banks, commercial banks, the rural banks to the APEX level financial co-operatives and their associations. During the ’90s, APRACA started extending its membership to MFIs keeping in view the important role being played by these institutions. Although we didn’t reach out to the smaller MFIs, we did reach out to the smaller organisations by providing membership to the national level microfinance associations, like those based in Pakistan, Myanmar and Cambodia. In a nutshell, we kept APRACA’s membership open for the institutions that were working for the development of agricultural and rural finance and MSMEs in the region.

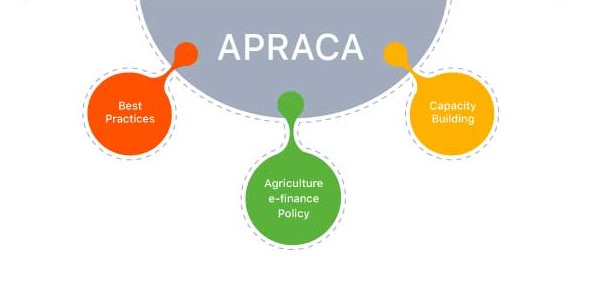

As APRACA has a very niche area of work, it takes up the membership with three primary objectives:

- We work with the policymakers, the government and the central banks so that we can have a rounded agriculture finance policy. We do this by generating evidence-based research in different countries, and the results of these are taken to the government.

- We try to document the best practices by the member institutions and then disseminate it to the broader knowledge portals which exist in FAO, ADB and World Bank.

- We also do the capacity building at three levels – one is at the national level where our member institutions find out some areas of their interest. At the same time, we develop the training modules and delivery, through our technical experts drawn from the member institutions. Second is the regional level which is more thematic in nature. For example, we are currently working on the green finance, SMEs and digital finance initiatives in specific regions. The last level is, of course, the global one.

For a public organisation, we are an incredibly open one! While our secretariat is in Bangkok, but we have our arms spread all over the region. For example, our regional training centre is in Manila, our consultancy service is in Jakarta, our Centre of Excellence in Beijing, the publication office in Mumbai and the Women Empowerment Centre of Excellence in Iran. We are also developing a centre in Nepal on Digital Finance and one in Thailand on Value Chain Financing. The secretariat’s job is to establish the relationships, maintain the network of partners and conduct their training need analysis. That’s my summary of the 43-year journey of APRACA!

Q) Could you mention a couple of remarkably successful initiatives that APRACA has led over the years? I’m sure there are many, but maybe the one’s you have been involved in person.

Prasun Das:

We have many of them indeed, and I can give you a couple of cases as examples. The Self Help Group (SHG) movement in India, which was started by NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) is an example of this. It was initiated by APRACA in five countries, with India being one of them. We received a GIZ fund in 1983, and we started working in Thailand, India, Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia. The most success that we got was in India, and it is now a movement, like in Thailand, where it is called JLG (Joint Liability Group). In these two countries, our mission was successful in engaging with the national developmental institutions to work with the local institutions.

The second example that I can tell you about took place during my tenure. We had a long engagement with the government of Nepal for three years. We were able to develop a policy in Nepal in financing the smallholder farming and allied activities, where they receive an interest rate subsidy of up to 5%, depending on the risk they were facing. For example, a farmer in Nepal who was in the mountainous areas had a higher risk, so his subsidy rate was more than that of a farmer in the plains. We developed such categories to determine what are the indicators of risk which would be accepted by the central bank, and now it has become a norm. The banks financing to the farmers under this scheme are receiving the difference through Nepal Rashtra Bank (the Central Bank of Nepal).

The third one, which is also a significant example, is where we worked closely with the Philippines government, along with the support of Agriculture Credit Policy Council (ACPC) and the Land Bank of the Philippines. Here, we supported the development of the terminal market, which is in Baguio City, for farmers. This market is now covering three provinces in the mountain region of the Philippines, where the highland farmers produce vegetables and bring them to the terminal market through the producer’s co-operatives. So they get a price which is better and higher than what they used to receive before!

Q) That’s excellent! Since you work with partners across the region, could you elaborate for our readers on some of the challenges that organisations into rural financial services face?

Prasun Das:

The key challenges that I see from APRACA’s point of view – has three parts to it. One is the Rural Finance Market Framework. The diversity in the Asian countries created a rural finance market which hadn’t grown and was ripe for disruption. For example, in India’s case, the agricultural finance market was deployed during the 1970s and 80s, and more emphasis was given in the 1990s when the new industrial policies came in. Other countries, like China, changed their policies in rural finance in the latter part of the 1980s, wherein they allowed the rural co-operatives to become commercial banks. The Agriculture Bank of China, which is one of the first members of APRACA, happened to be a co-operative bank and now they’re the second-largest bank in the world!

There is much diversity which is a real challenge to the whole agricultural finance market in South Asia and Asia Pacific region. Within the rural finance markets, we have issues like the development of differential products. We have several financial products to support agriculture; however, if you go deeper into those products, you will see that they are mostly general and not customised, which is what the agricultural sub-sector requires. To address these challenges, APRACA is developing tailor-made products for the fisheries sector along with FAO. If you go to the banks in India, Cambodia or the Philippines, they don’t have any particular product for the fisheries sector. So now we’re trying to develop such a product for the industry. As you know, insurance is an essential component in the agriculture financing sector, and only in some of the countries like China and India, do we have insurance-linked loan products. So we are trying to build a similar product to develop for our fisheries sector – an insurance-linked fisheries lending product.

We have also seen significant issues related to KYC (Know Your Customer). On the one hand, you have some countries with strict KYC norms due to the terrorism-related threats, and on the other, there are countries with no rules at all! Another challenge is the limited financial access issues like in Nepal, which is mountainous, and the banks have their branches in city areas. These are some examples of the challenges we have to address with the use of technology, favourable policies and regulatory reforms.

Rural Financing regulatory framework is another area of challenge that organisations in this sector have to face. Some of our central banks are very developed, and they want to move forward quickly. An example is the Bangladesh Bank which has made changes in the last ten years to enable agriculture and rural finance, and their progress is impressive. Even bigger countries have not been able to achieve this level of success. Another example is from Cambodia, where the Central Bank there has developed a cryptocurrency.

The government and the Asian countries are intervening in the finance market vastly because most of them have policies of their own. Some of these are demand-led, while some are subsidy led. These rural market regulations have always been an issue for us and a large amount of APRACA’s time goes in engaging with central banks for enabling such policies. Even if the challenges of the rural finance market and regulatory frameworks are addressed, one will would still need to innovate mainly at a product and services level.

To elaborate a bit more on this aspect, let me share the learnings from a project that we did for four years with IFAD on documenting best practices of rural financing in different countries like India, China, Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand. What we found is that one state may follow excellent practices in agricultural finance and outreach, but it does not suit other countries. The issue of innovation comes in here – how does one innovate to add features in the product of one country and implement it in another?

Although there are issues of innovation, lately there have been good signs of exciting products being developed such as the micro agricultural loans in the Philippines. The rural banks there have designed micro agriculture loans for amounts as low as $ 150 – $ 200 and these may last for a period of 7 to 10 days so that one can come back and repay it comfortably. This is an important innovation as the bank can immediately serve the customer with the requirement. Even micro-insurance as a product didn’t receive recognition until 2010-11, and APRACA took many efforts to engage with the banks and insurance companies to develop these products and deliver them to their borrowers.

We recently carried out a study for green finance in the region to understand how “green” it is and whether these new products are serving the agriculture sector or not. We found that these weren’t directly serving agriculture. However, indirectly they did, and we have to understand the reality – which is that the agriculture sector produces greenhouse gases. We need to develop a product to curtail this aspect. Hence such innovation is essential, and now we are looking to work with CGIAR and the Stockholm Environment Institute for developing a green finance product for our members.

Q) Can you also throw some light on the challenges faced by the rural financing sector due to COVID lockdowns? And how do you see the current situation evolving moving forward?

Prasun Das:

Recently we surveyed our member institutions and came across some key issues. One of them is servicing the smallholder farmers for providing them with necessary inputs, provisioning of markets and including procurement, and insurance. Due to the markets getting disrupted, smallholder farmers across countries faced the maximum brunt of it. Hence, it’s clear that we need to find ways to provide them with digital agricultural technologies. We also found that the livestock market was more affected than the agriculture market, and I believe that we need to ensure that we stabilise their demands, as it was highly unorganised.

It was apparent to us that we needed to provide a significant amount of financing facilities to the value chain actors, who are in turn providing services to the smallholder farmers (SHF) by buying back produce or providing them inputs. These are the small agribusinesses and even AgTech startups who are serving SHFs. Hence, our primary activities during the COVID-19 time was providing tailor-made solutions to the SHF’s so that they can avail the required money to pay for the labour. These agricultural labourers were in distress and weren’t getting their farm job back, while they aren’t supposed to keep their produce in the field for a long time either. Hence enabling financing to them is essential so that they can have a linkage with the buyer at a village level, which supports the local food system. APRACA is working on initiatives to unlock financing for these small groups who are taking care of the products from the field.

We also supported the small businesses so that they could link up with the larger stores and so that they can get a more extended period of cash credit from the financial institutions. Most of the cash credit these groups were getting was for two or three cycles, which has now increased to five to eight cycles. There is a requirement of huge investments, but our financial institutions are facing considerable challenges currently with assets and liabilities because the asset sizes that they have created is no longer working, due to rising delinquencies as an after-effect of COVID-19.

During this lockdown and due to restricted movements, the savings chart which the Asian Development Bank has published recently shows that the propensity to save has been reduced, with rural markets being drastically affected. This is a particular area of concern from a financing point of view, and most rural banks would suffer as well for the near term at least due to these cash crunches.At APRACA, we tried to negotiate with the central banks to support MFIs or NBFCs in Cambodia, for example, by conducting webinars with all of them and guiding them on how to deal with this pandemic situation. In Bangladesh, a small fund for these NBFCs and MFIs was created so that they can get funds from the central bank at a low interest and for a more extended period. These are some of the things we are doing to support our member institutions so that they, in turn, can help the farming community and the rural population in their countries, with the outlook that such downturn will be the new normal for the next couple of quarters.

Q) Regarding the challenges that you mentioned, there are so many different aspects around. You also spoke about linking insurance to credit which is somewhat done here in India, although the current insurance scheme is now voluntary. Another major challenge that we have seen in India is the absence of digital land records; it is so challenging to create a customised product because of this. We have to go to the lowest administrative region – that is the village boundary. Is that something prevalent across the broader Asia Pacific regions as well?

Prasun Das:

You have brought up a fundamental issue, and we have been grappling with this over the last five-six years. What we have found that is, even countries like India and China face such problems. Smaller countries like Thailand have, however, digitised their land records, which are an asset for them today.

We suggested to the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India in a recent meeting that we not only need to record the land size but also the record the other assets in a registry. Having such a log at a national level for the farmers, where they can register their land, all their assets like how many cows they have, how many cycles and their updated value will prove to be vital in unlocking more finance in this sector. This would help to finalise what is the worth of a particular farmer. If the value is estimated basis just the land, then that is not reflecting the real worth of the farmer. We have seen some countries are trying to do it – though not in the Asia Pacific region.

Our counter agency in Africa created such a national registry where they had registered all the farmers. They then categorised them based on the asset’s quality, size and worth. This would help any financial institution, including an insurance agency, at any point of time to understand the value of this particular farmer.

A new workaround on the challenge of missing digital land records was seen in China. They developed loan insurance a kind of guarantee, as digitising every farm is a mammoth task which may not provide the right benefit even for the cost needed to achieve it. Today, loan insurance is a particularly important market in China, and it isn’t insurance like what we see in India or the Philippines. One doesn’t have to go to the farmer; instead, companies providing these loan insurances have to do the due diligence on the bank and the portfolio of the bank.

Several innovative ideas are coming up. But the collective agreement is that a digitised system to show the worth of the farmer is the most important activity that needs to be achieved for the insurance companies and banks servicing the agriculture sector to survive.

Q) You mentioned about evidence-based reporting, which is something that APRACA does. How do you see the use of alternate data like weather proxies or satellite imagery for doing this kind of reporting, especially in the context of a post-COVID world where travel restrictions will be there?

Prasun Das:

We all have seen that the banking infrastructure is changing rapidly today, with more and more penetration of digital technologies. About ten years back, we were thinking of the national ID, which is very important in many countries, like India and China. The national ID was essential to identify the borrower, but what we have found is that even if a national identity exists, it is not enough to push for enhancing finance in the agriculture sector. A deeper dive into this was taken by us to look at the elements needed for a financial institution to identify when they want to finance agricultural development or projects. We found that it isn’t the national ID or KYC but the changing environmental situation.

There are three challenges in this respect. The first is that agriculture in several countries is dependent on the weather. The second is regarding the off-takers of these agricultural commodities which the farmers have produced. And the third issue is that it is not just the off-takers information that we need but also that of the whole value chain ecosystem. All these three things need data. Without useful data, it is not possible to address these gaps.

Now agriculture is a technology-driven sector, and all of our member banks understand this. Unless you consider data as necessary, it will be a precarious affair to finance SHFs, who constitute the majority of the farming community in Asia. But if we have accurate data, for example, the information regarding the crop and weather patterns from the past ten years, we can start predicting on what might happen to the crop of the farmer who is borrowing.

It is a known fact that data will play a significant role in the next five years. We at APRACA are trying our level best to include all our financial institutions, including the banks, to provide guidelines to our member institutions so that there will be a considerable usage of the data – both traditional and alternative ones. There is a large amount of data available, but in a lot of the cases, it is not centrally stored and may not be readily available to the banks. But private-sector banks can get the data from various organisations like SatSure, for example, and use it for their work. Data will be the next level of change in the banking system, especially for rural banks and agricultural finance.

There has also been considerable talk about ESG (Environment Social Governance), where we are telling our banks to consider this in their risk mitigation process. For ESG, we need data and how this data is generated and used should be decided at a national level, which we are facilitating. What we have found is that if obtaining the information is expensive, then our smaller institutions like financial co-operatives and MFIs or NBFCs – they would not be interested in using it. But if the data is available at a commonplace, at a national level where they can access it easily, then it will be easier for such institutions to involve themselves in this system to get the data and make informed decisions.

Q) What we have seen in India is that NBFCs and MFIs, even though their loan sizes are small, are keener to adopt technology than the large public sector banks. Is that something you see in the Asia Pacific region as well, where most large central or public banks are slightly more risk-averse in trying out new technologies?

Prasun Das:

You are right. Most of the large banks in this region are government banks. Till they don’t receive directives from the government, they won’t take up any new ventures. However, NBFCs are talking about it. For example, in India, one of the NBFCs is Samunnati; they are taking up a lot of these new initiatives. They are considering the data as a significant driver for their financing to the value chain. The data is not just for providing funding to the farmers, but also for making decisions about other actors in the ecosystem.

Back to your question, yes, most of the large banks in the Asia Pacific region are minimal adopters of such technology, but when they do adopt it, they do it in a big way. We need just to wait and keep providing them with more data or feedback or evidence so that they will adopt it, and when they do, it will be huge!

Q) This brings me to the last question, which is related to the role of developmental agencies like IFAD, FAO, ADB in these testing times for supporting agricultural finance in the region. You mentioned that the delinquencies have been high, and the asset quality has overall reduced for lenders in the area. How do you see developmental agencies playing a pivotal role both from a policy perspective and technology guidance? As you know, the developmental agencies are the ones exposed to all kinds of technology and policy reforms that are provided as a consultancy to the members. How do you see these entire dynamics evolving?

Prasun Das:

You have raised an important question! However, what I would like to flag here is that majority of these developmental agencies work with the government and not the lenders. For example, the multilateral agencies, work with the government while bi-lateral agencies sometimes work with the private sector. These agencies have two powers – one, as you said, is the development aspect, the other is their businesses.

When we talk about this post-COVID-19 situation, what we have found is that in most of the Asian countries, agriculture faced a formidable challenge to grow. Asia has the highest population growth rate, and interestingly the highest growth rate of agriculture as well. The Asia Pacific region is the largest exporter of different food items across the globe, so we need to be more focussed on developing our agriculture to be at the same point as we were before COVID-19 happened.

A harsh lesson that we’ve learnt is the challenge of technology in infrastructure, especially that of warehouses, and cold chains. Farmers will continue to produce, but the prices of their commodities are reducing each day. At the same time, the people at the end of the value chain are getting the product at a rate higher rate. Why is there such a big difference?

We did a study in where we saw that a farmer who produces the same product that he was in January, is selling it in June, at a 66% higher rate than what he was selling in January. There is such a big dichotomy here, and we need to help the farmers to get the right balance. So with this problem identified, here comes the role of the developmental institutions.

These agencies can provide technical assistance where they can support the farmers to become significantly more competitive in the current scenario and assist them in linking it with the market. Also, developmental financial institutions like ADB need to develop agricultural infrastructure to support the farming community so that SHFs can get the right kind of a price through such infrastructure development. By infrastructure, I mean not only physical ones but also the technological ones where they can get information about the market, about the weather, the prices of the inputs and outputs. We’ve been trying this for some time. If one does a check today, you’ll see that farmers haven’t been able to reap the benefits of technology as you would expect.

So, what should be the mechanism to execute this? For example, in Vietnam, the women’s co-operatives are a significant force in the whole Vietnamese agricultural export system. Vietnam is now exporting the highest amount of agrarian commodity in SE Asia. How did they do this?

We need to draw lessons from such kind of models and put it forward to those development agencies so that they can support other countries. What I have seen is that the development agencies are doing much work in this COVID situation. For example, IFAD created a separate fund for less developed countries to build their agricultural value chains, so that the local market doesn’t get disrupted. But there is still a lot more to do, especially working closely with the government. We have discovered a ground reality, and all of us need to watch closely and work from there.

This article was first published in The SatSure Newsletter

Add comment