About Crop Loan

From ancient times, Indian farmers practised subsistence farming (i.e., farmers produced what was needed for their immediate family, but not to sell in the market). This is the foremost reason why farmers from ancient times couldn’t accumulate large amounts of wealth. Slowly as the British and globalisation took over, the Indian farmers were forced to produce a marketable surplus. However, the repeated famines, non-remunerative prices, miscalculated policy actions, and many political agendas ensured farmers remained hand to mouth. Various reports have pointed out that the farmers’ average annual income hovered around Rs.70,000 to Rs.80,000 during 2012-13.

Further, the income levels increased with growth in acreage. The average Indian farmer holds small or marginal landholding. All this points out that one of the major threats to the Indian farmer is the lack of investment for farming activities. Despite this constraining situation, the farmers have continued to invest in their farms by borrowing from various lending parties. Until today, informal money lending remains a widespread means of agriculture finance. However, it is steadily being replaced by formal lending institutions like banks and NBFC’s. Despite the new age policies taken to push farmers into taking credit from formal institutions, the method of assessing creditworthiness is still archaic.

Existing Process

The farmers would need the crop loan before the beginning of the crop season. The farmer could approach the banker either for a loan renewal or a new loan. When the farmer approaches for a new loan, he would have to submit documents to prove that his land is non-encumbered and a no dues clearance certificate from all the banks in the service area. If a farmer attempts to obtain renewal for the crop loan, then he would have to submit a document confirming his ownership of the land and fill up the application form. The application form contains details related to acreage, type of crop, farmers’ capabilities, etc. With these documents in hand, the banker proceeds to determine the creditworthiness (CW) of a farmer.

The three main components in deciding the CW of a farmer are his CIBIL score (also known as CIR – Credit Information Report, issued by Credit Information Bureau India Ltd, referred to as CIBIL), past performance on loan repayment and the inputs received from the informal network. Using the above factors, farmers CW is determined and combined with the ‘Scale of Finance’ to arrive at each farmers’ loan eligibility. The scale of finance (SOF) is a document prepared by NABARD’s (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) State Level Banking Committee (SLBC), determining the rules and limits of agriculture lending.

In addition to this, it has been observed that farmers’ relationship with the bank managers might determine loan eligibility. Upon completion of all these intricate procedures, the bank communicates its loan acceptance decision to either accept or reject a crop loan application. At this stage, the banks’ field level officers are expected to step in and do the groundwork. This involves verifying the farmers’ details based on the field visits and also discussions with village-level informal networks.

The loan is then disbursed to eligible candidates, and the bank is supposed to monitor now and then. They accordingly provide interest rebates under government regulations. The Interest subvention (IS) and the Prompt Repayment Initiative (PRI) for the short-term crop loans determined by RBI (Reserve Bank of India) are 2% and 3% respectively for loans up to 3 lakhs. This implies that if a bank charges interest for crop loan at 7%, then the effective interest rate for a farmer who borrows less than three lakhs would be 2% (i.e., 7% – (2%+3%)). The 5%, which includes the IS and PRI component, would be remitted by the government, and the bank would need to collect only the remaining 2% interest from the farmer.

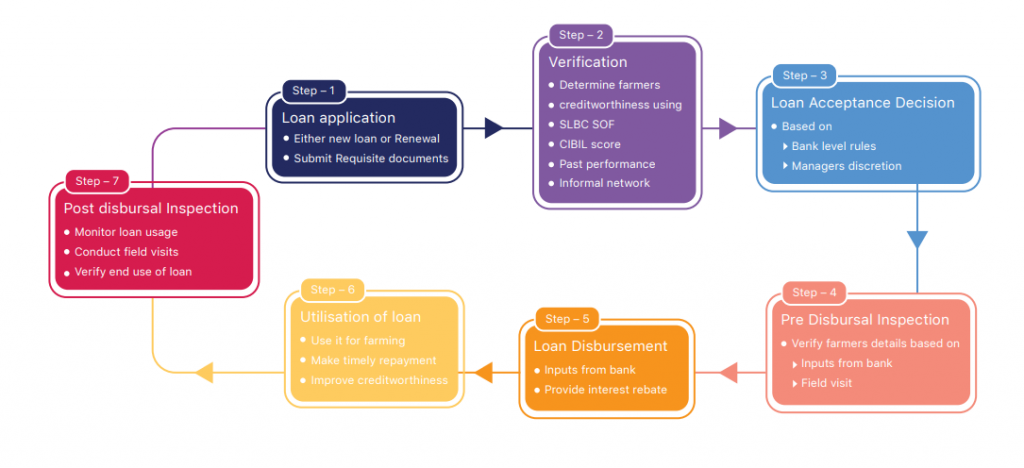

In this stage, the role of field officer is again crucial when they perform post disbursal inspection. They would need to conduct field visits and also monitor the usage of crop loans in accordance with the loan application. The farmers, on the other hand, would receive the loan amount and are supposed to use it for their farming activities. Making timely repayments would also be necessary to improve their creditworthiness for being able to renew their subsequent credit. We have captured this whole process diagrammatically in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Existing crop loan management process

Inefficiencies/Limitations of the Existing Process

After discussing with various stakeholders, we understood that the above process has serious inefficiencies. Every bank has priority sector lending targets, and they would want to attend to them. Quality is compromised in the process of increasing the number of loans. Our observation reveals the following:

- Substandard way of determining creditworthiness (Step -2)

In Step 2, the banker would have to verify the application and documents submitted by the farmers and determine their creditworthiness. Although the bankers are guided by Scale of Finance and CIBIL score, the bankers do not take into account more efficient micro-level farmer data which could help them better understand the farmers’ repayment capability. For instance, data on farmers’ past performance or the existing/forecasted market conditions for the crop in question are not being considered. These two pieces of information are very crucial and hence if missing, would lead to a substandard determination of the farmers’ creditworthiness.

- Manual discretion coming into the picture (Step – 3)

After getting a reasonable idea on the farmers’ creditworthiness, the final call of whether to give a loan or not is still dependant on the bank manager. Many studies have vouched for the prevalence of discrimination in rural India. In these lines, if a bank manager discriminates based on gender or caste, then even an eligible farmer could be deprived of loan. Although eliminating manual discrimination in these decisions is currently farfetched, at least amending the manual component with objective evidence would help in tackling such discrimination.

- Pre disbursal inspection being overlooked (Step – 4)

The official norms of the banks require the field officer to visit every farm before loan disbursal to check upon the farmers’ whereabouts, the land, and other information contained in the loan application form. However, we observed that field officers rarely perform this job. Especially in the cases of loan renewal, the loan is granted merely after the farmers visit the bank and fill in the application form. The reason for this could either be the laxity of the bankers and the lack of adequate staff. Given the limited workforce available and wide range of farmers (and their acreage) to be covered, strict and wholesome background checks become close to impossible.

4. Post disbursal inspection being given a miss (Step – 6)

This is another area of grave concern. Several farmers divert the proceeds of loan several times for non-farming purposes. They would mostly use it for purposes such as the marriage of their children, education, constructing a house, etc. Some have reported that they would use this money to lend to other villagers informally and earn interest from it. This diversion happens because the field officers give the post disbursal inspection a miss. There have been cases where the banker is aware of such diversion but tend to overlook it as long as they receive the payment within time. However, this has the potential to defeat the real purpose of crop loans. This also provides an implication to the policymakers to introduce other convenient credit options for farmers’ purposes and ensure strict guidelines for crop loans.

Owing to this inefficiency, farmers who are looking to expand their activities to higher acreage would not obtain higher crop loans. Almost all farmers we interviewed made use of crop loans, but many of them still depended on informal money lending because the crop loans had an upper limit. Hence, with proper monitoring, more crop loans can be given to deserving farmers, which in turn would help them increase their income.

Intervention – Satellite Imagery Analytics

The formal lending is expected to increase in the coming years. The lending institutions would slowly start recognising agriculture lending, not as a compulsion but a viable business vertical. For that to happen, the creditworthiness assessment and credit collection have to improve. At this stage, satellite imagery analytics has a crucial role to play.

Satellite imagery analytics can map the entire loan life cycle across the crop life cycle by monitoring crop health, soil moisture using satellites, and weather data. This helps the bankers to determine and analyse cropped acreage, yield predictions, availability of ground and surface water and price movements.

Re-engineered Process

We estimate that the satellite-based data analysis can cut short the existing crop loan process and also drastically improve its overall efficiency. In the revised procedure, the farmers submit their application for crop loan to the bank. At the stage of verification, in addition to using CIBIL score, past performance and informal networks, the banker can rely on the insights from satellite imagery analytics to extract detailed information on the past performance of the farm and thereby understand farmers’ prowess. This would aid the bank manager in step 3 to take a more informed and objective decision. This input, to some extent, will also help in tackling the discrimination existing in the loan disbursement process.

In step 4, the field officer would still need to visit the farm but will be able to make better decisions with satellite imagery analytics aided tools. Currently, the role of a field officer, although necessary, is being side-lined. This inherent limitation in the current process will give rise to severe inefficiencies. Once the loan is processed with inputs from satellite imagery analytics, the post disbursal inspection could be ultimately taken over by satellite and drone technology. Satellite imagery analytics can regularly monitor the performance of the farm. This would reduce the requirement of regular field visits, hence decreasing the loan life cycle management cost to the bank, which can potentially be passed on to the farmers. This in turn will also help the banker to assess if the loan proceeds are only being used for farming.

Further, due to constant monitoring, the bankers could well understand the trend of the market price. This information helps in loan recovery. As satellite gives a clear and accurate picture of what happened in a given land, the loan recovery officers could argue with facts and achieve higher recollection. In case of loss at the farm due to environmental factors, the banker being equipped with a better understanding of the reality, can be more empathetic to the situation and find a better solution that involves cooperation on both sides. Figure 2 presents the re-engineered crop loan management process after the intervention of satellite imagery analytics.

Satellite analytics can also help in sourcing of farm loans more transparently. It can help a banker to expand his portfolio while reducing risk by lending in areas that have shown improved performance in the recent past. This process would reward those farmers who have been working hard and applying better land management practices that lead to better utilisation of the land. This also gives confidence to the banker to expand his loan portfolio in a way that does not lead to increased risk.

Takeaways

Satellite imagery analytics has the potential to provide a universe of information to the bankers regarding crop loan. This can potentially reduce the significant overload on field officers. On the long term, there would be increased discipline among farmers and bankers would be able to provide higher loans, thereby easing the access to credit for farming. This would also reduce the dependence on informal money sources. Going forward, this can be a significant step in bridging farmers and bankers to achieve the intended objective of instituting low-interest crop loans for farmers.

Written by Reddy Sai Shiva Jayanth, Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode, India; Dr Gopalakrishnan Narayanamurthy, University of Liverpool Management School, UK; Roger Moser, Macquarie Business School, Australia; and Narayan Prasad Nagendra, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany

This story was first published in The SatSure Newsletter

Add comment