Introduction:

Dr Vinay Kumar Dadhwal is former director of the Indian Institute of Space Science & Technology (IIST). He has more than 37 years of research experience in developing applications of earth observation data for agriculture, hydrology, land transformation and deforestation and disaster management support. His earlier leadership positions include Director, National Remote Sensing Centre, Dean of the Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IISR) and Head, Crop Inventory & Modelling Division (CMD) in the Space Applications Centre (SAC/ISRO) during 1998-2004. He is a recipient of many awards from ISRO, Indian Society of Remote Sensing, Indian Meteorological Society as well as young scientist awards of Indian National Science Academy (1989) and Indian Science Congress Association (1986).

Q) Let us begin with the story of how you got into Remote Sensing, specifically Agricultural Remote Sensing?

Dr Dadhwal:

It is indeed, a story! I had done my Bachelors in Botany from Hansraj College Delhi University. There used to be a competitive examination known as the “ICAR Fellowship”. Here you wrote a national exam in one of the agriculture subjects and being from a Botany background, and I had appeared for ‘Plant Physiology’. In 1976, the fellowship holders were invited by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) for an interview to join the master’s program. That is how I joined the M.Sc. in Plant Physiology at IARI in 1976.

After completing my M.Sc. in 1978, I took up a PhD. My research covered “A study of phenology, growth and yield in Wheat concerning environmental factors, especially photoperiod and temperature.” During this period, the only remote sensing topic I came across was LACIE – Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment of USDA, NASA & NOAA.

In January 1983, the Space Application Centre (SAC) visited IARI and held in-campus interviews. They were looking for Agriculture or Agronomy students to do wheat yield modelling. I had appeared for the interview, and so without a formal remote sensing education, I joined the Space Application Centre on 30th June 1983 as Scientist SC. The division that I worked in was called Aerial Surveys Ground Truth and Photo Interpretation Division (AGPD) and was headed by Dr Baldev Sahay.

The first job that was assigned to me was to demonstrate a procedure for groundnut forecasting. In September of 1983, ISRO formally started a programme called “IRS Utilization Program” which had 16 projects. There were four operational projects and four quasi operational projects which were assigned to the National Remote Sensing Agency (NRSA) in Hyderabad. There were four experimental and four technique development projects which were to be carried out at SAC. One of the experimental application projects was crop production forecasting. So along with Mr Jayasingh Parihar, M.H. Kalubarmey, Dr M.V. Poddar and myself – we formed the first satellite-based crop production forecasting team.

Over the next 21 years, I developed many procedures. These were for a village level to national level satellite-based crop forecasting and included crop discrimination, assessment, yield forecasting and crop biophysical parameters.

Q) That’s very interesting, sir! You have come from a botany background to a remote sensing background so seamlessly the way you have explained it.

Dr Dadhwal:

Yes, none of the work that I have done has been repetitive; they are linked but still dissimilar. Same plants, same crops and same objective but the tools and processing changed continuously. We were educating ourselves on the new tools, along with the regular forecasts the team was carrying out.

Q) True! An interesting observation that our readers would have is you were part of this crop forecasting team way back in the early ’80s, and today we are in 2020 and are we still speaking of the same thing?

We are attempting the same objective with new data, approach and an entirely new system design. If you look at the Mahalanobis National Crop Forecasting Centre (MNCFC) website, currently for nine crops and 14 states, they are doing multiple operational forecasting.

So the Remote Sensing based assessments are slightly different than how we generate bottom-up traditional crop statistics. In that approach, village enumerations are added to create the estimates for blocks and districts. The average yields of districts based on crop cutting are used to get the state and national level crop estimates.

Q) There are many industrial applications of crop yield forecasting – and the current shift we are seeing is to go from district level forecasts which MNCFC was doing to GP level yield forecasting which is currently being piloted by them. The next step that would be to do farm-level crop yield forecasts. What do you think needs to be done from data acquisition, remote sensing, and crop modelling innovation to get to farm-level yield forecast? Or is it a pipe dream, in your opinion?

Dr Dadhwal:

Firstly, there has to be a purpose to do a farm-level yield forecast. Secondly, one of the early lessons we learnt was that the cost of making a forecast must be less than the benefit which will come from the estimates. If the cost-benefit ratio does not support a projection, then it will die.

The third important point to remember is that a forecast is temporary – it will die when another late-stage estimate or the actual result is found. Fourth – the forecast’s accuracy will be a function of how early/late one is making it. The best forecasts are those which are taken in a later stage, and also accounting for what is likely to happen from the date of the forecast to the actual harvest. So, if you are making a forecast 60 days before the actual yield, it will have more considerable uncertainty. If it is 30 days, the risk is less; and if you’re making 15 days before then, it is quite likely to be entirely accurate.

Now let us talk about a spatial scale – farm or district. So, when you are standing in the field, you can use biometric and some local input like weather to make a forecast. You are seeing the number of stems bearing grains, length and other such biophysical parameters. Nowadays, you can use a mobile phone to capture the information to be analysed by machine learning. Suppose the aim is to do a GP level or a village level forecast, the sampling points matter – how they account for soil and plant variability. The moment you go to a district-level, you have two challenges.

One is choosing the areas where you would do stratification and where you would do the complete enumeration. But data such as soil type, date of irrigation or application of fertiliser, would be available on a nominal basis. So, you have to start making intelligent solutions. This way, you can either end up in an empirical statistical model or an advanced model if you bring in crop simulation models. When you have, for example, a better medium-range weather prediction, you can bring in the forecasted weather also – and then you have a much higher version of a forecast. Second is, assimilating the satellite-based biophysical parameters (Leaf Area Index, phenology and biomass) then run simulations with multiple downscaled weather forecast. An empirical model can only be applied to the similar data set and the same location, the same set of observations. But advanced models can be easily transferred across spatial and temporal domains.

Q) Just out of curiosity, I would like to understand what kind of time scale that should be targeted for doing the appropriate model based on phenology. The reason why I’m asking is that during Kharif season we have to do a gap fill – we have long durations of no data. So phenological detection can also give inaccuracies. So, in your career as a practising remote sensing scientist, how can one achieve the best temporal resolution to achieve good forecast accuracy?

Dr Dadhwal:

Even if one goes to the field and makes a phenology observation for an area, the uncertainty would be +/- 1 to 2 days; this sets an upper limit of the accuracy required. With Earth Observation (EO) data which is available weekly is a full corrected time series that can be interpolated, then it could allow phenological estimation with +/- 2 to 3 days.

The challenge of a scientist is using multiple pieces of evidence because actual sowing day will not come from remote sensing, but you will get spectral emergence. So, you will get a profile of growth, which is every week or every 2 or 3 days. If you can convert spectral emergence into an expected sowing date and also parallelly do thermal imaging, then you can use this convergence of evidence to get +/- 2 days. This should solve most of the challenges.

Q) I would like to go one step back to where you were talking about your journey. You have had a long career path where you have worked in SAC, and then NRSC to heading IIRS and today you’re in IIST. How and why did you go from NRSC’s industry-focussed application approach to more of training the next generation of remote sensing experts and scientists at IIRS and now at IIST?

Dr Dadhwal:

Let me confess that I haven’t consciously done anything. Whenever anything that posed a challenge has come my way, I have taken it up readily! So, while I was in SAC and was heading the crop modelling division, Dr Navalgund, then Director of NRSA asked me one day if I would like to go to Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) in Dehradun. He explained that as I am research-minded, the place will suit me and so, I decided to go.

So, I did agricultural remote sensing in IIRS until I was invited by Dr Radhakrishnan to go to the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) in Hyderabad and take up a different responsibility. In 2010 I came to NRSC to be the Associate Director and oversaw many of their duties until 2016. In the year 2016, I came across this advertisement put out by IIST for a similar post. I was initially hesitant to take it up initially as it was engineering. However, people advised me as I’m interested in research, and education and I know so much about space and remote sensing – I should take it up. So, I went ahead and applied for the position on their advice and got it.

Q) So that is how you became a part of IIST! Us alumni are very thankful that you’re there as a director leading the institution. There has been a lot of changes and growth during your time, especially with the moves to open up to industry, setting up a placement cell, and the courses undergoing modifications.

We at SatSure have hired many IIST graduates as well since 2017, and quite a few of them are at leadership roles currently. How do you see IIST playing a role in bridging the industry talent gap, especially with geospatial technology becoming more integrated with traditional software products and applications?

Dr Dadhwal: Frankly speaking, a Director has limited functions. He has to ensure that the faculty teach, the students learn, and he facilitates the work of every individual.

A challenge that I have seen is that this domain of geoinformatics where the industry-academia gap is ever-widening. Earlier it was just surveying or satellite data interpretation. Now the areas of navigation and positioning are becoming critical. When you study engineering with a strong foundation of physics and mathematics, you can apply your mind to any tool. You are ready to assimilate the information from different domains and solve a problem. So, at IIST, we emphasise on problem-solving skills rather than knowing a software. Knowing a software implies that you are a technician and IIST doesn’t produce technicians, it creates engineers who possess problem-solving abilities in mathematics, programming and interdisciplinary areas. Through their internships which begins from their 2nd year, they come across innovative ideas in their field.

What we have also done to our engineering students is to provide more options through a choice-based credit system. We have also recently started the industry partnership program for them to collaborate with companies from an early stage in their curriculum while also being mentored academically by a professor at IIST. The industry partnership program is a step towards making IIST an attractive place for companies to recruit.

Q) That is a fantastic initiative, and I am sure it will benefit both the students and the industry collaborators.

In the geospatial industry, what kind of innovative applications would you say could be developed with the introduction of new technologies like high-frequency satellite data, cloud computing, and AI?

Dr Dadhwal: In the industry, the individuals would get segregated into traditional RS/EO analysis and those who would do LiDAR/mobile vehicle survey. These come under the domain of photogrammetry and information extraction and merging with geospatial datasets. The latter category’s skills are becoming more critical as a part of extensive infrastructure monitoring like buildings, roads, and bridges. So, we would see a high amount of collaboration between the engineering and architecture teams with the use of geospatial technologies.

On the other hand, smart cities will be coming up, and they would be linked by sensors, decisions and SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) or IoT (Internet of Things) and real-time data. The third domain will be citizens and NGOs who would use one’s phone to take a picture and acquire some information. The information obtained can be used for providing the community information, for example on underdeveloped areas and places which aren’t safe for women.

The fourth category is the application of geospatial technologies in water resource management, irrigation, the distribution and use of pesticides, protecting the forests and preventing fires. Finally, we have an application in global-scale problems from monitoring greenhouse gases, the size of the poles and protecting the oceans. One wouldn’t be able to do all this daily without the widespread use of geospatial technologies.

Q) Correct, like the use of Google Maps on one’s phone where one doesn’t realise that their location is the result of triangulation of four GPS satellites.

Dr Dadhwal: Yes, everyone uses Uber and Ola; they don’t realise that they’re using geospatial technology. They only ask the driver to come to their location! There are even algorithms for taking the shortest route from your location to the next.

Q) I agree. India is doing well in the geospatial domain but not at the same level as other developed countries. So, many people blame the non-predictability and the non-transparency of the regulatory framework around it.

In your opinion, especially with the establishment of IN-SPACe, which has led to both positive and negative vibes everywhere, what role do you see the government playing in shaping the convergence of geospatial technologies into mainstream software platforms like mobile phones.

Dr Dadhwal:

Let us look at the answer in this manner – you would agree that there are successful geospatial companies in India? There exist technically competent geospatial organisations who carry out projects for global users. We also see other successful organisations who own the content, like MapMyIndia. We also see implementations done in-house like electric utilities and the construction of Lavasa, to name a few. Either one owns the content or has the expertise or they should build up a customised system.

I have come across many individuals who say that interpreting the scene or acquiring high-resolution data is their biggest challenge! I would say that it’s the least of the problems, especially if you want to be a top-notch commercially successful organisation. The critical question is – what are the skills necessary to do this? The policies and the government are looking from the perspective of security and marketing their data. There are ways to go around these challenges – which are both successful and financially viable.

Q) Yes, that’s true, at SatSure we have also been able to work around these challenges and create a sustainable business!

Dr Dadhwal:

What will change post this pandemic is that it will become effortless to access and market high-resolution satellite data. For example, the locust attack on India has shown that agencies can simply hire drones and spray insecticides; even the Survey of India used drones to do cadastral and field mappings.

An entity’s commercial success will be based on the software they use; the content they deliver; and the service the end-user subscribes to. An organisation needs to answer three essential questions – what are they bringing to the table, where do they fit in and what can they uniquely sell to users and ultimately make money.

In my opinion, the policies are nice to have, although they can only do so much. The actual business acumen, the technologies and solutions one brings to solve people’s problems and to make money simultaneously – that is the essential skill needed in the industry. They need to create their own markets!

Q) I agree! We are seeing that the usage of open-source data and satellite data from the European Space Agency and USGS has played a significant role in making the focus more on creating market demand. However, what many people don’t understand is how the interpretation of the information that they are getting could convert into final insights.

If you could provide, based on your experience, what are the key pitfalls that start-ups operating in the remote sensing & analytics space should take care of in their technology development plans.

Dr Dadhwal:

The supplier and end-user must answer three crucial questions: what exactly is the information needed, when is it required and what would be the format for assimilation. When I was the at NRSC lot of people would question the absence of high-resolution data. They miss the point of the resolution required for their application and the limitations of large area coverage at such a high resolution (in that time frame). Also, USGS and ESA opened their data, and commercially available data remained at a substantial cost.

The second issue is that most of these applications create legacy data. So even a new map may still have 80-85% accuracy. However, if we assimilate past maps and field information in the next cycle of assessment with appropriate logic, a better output could be generated. Thus, legacy data availability and use must be encouraged.

Q) You mentioned an interesting point that many people don’t get. Two out of the four founders at SatSure did not have a remote sensing background, so we started with wanting to understand the customer problems and then work backwards to create the most optimal solution. A satellite image may not be the only way of solving that problem. Over time we arrived at something through a rigorous process of customer discovery.

So according to you, what are some of the more significant problems today which could make use of such kind of a service-driven by remote sensing data and also has a nationwide impact? Could it be better yield prediction, could it be creating better models for monitoring infrastructure construction, or something related to supporting sustainability initiatives of the government?

Dr Dadhwal:

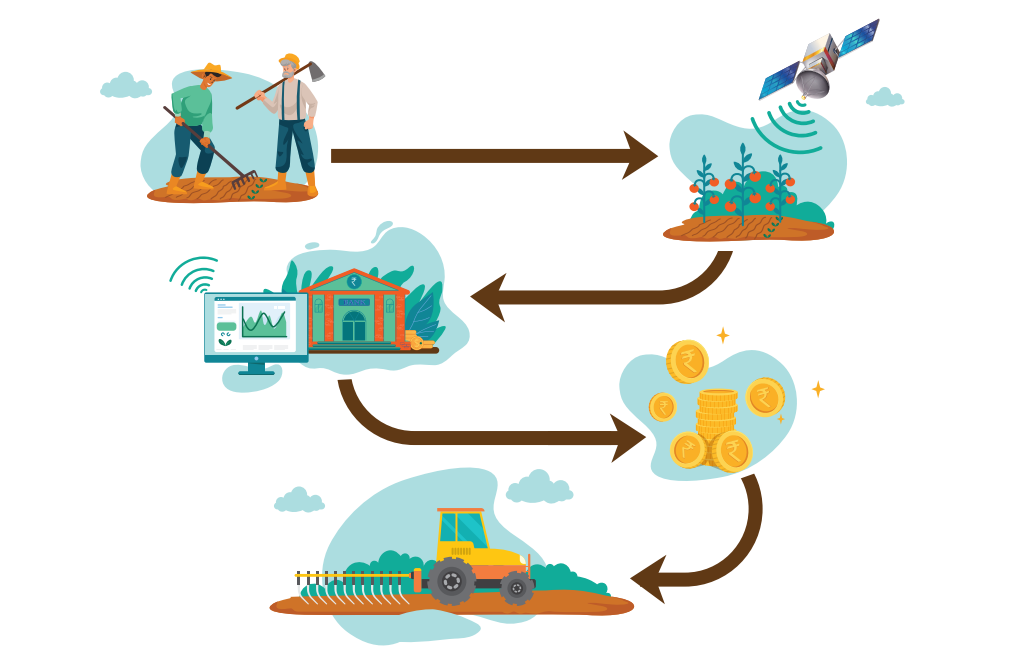

In my opinion, if you want to address a problem like making a national level forecast or a state-level forecast, you will have limited users. But suppose you want to make an impact; it is always good to have a product which one can modify at two or three spatial scales. It can be tweaked at the farmer/village level or the local supplier level, depending on the kind of problem you want to solve. Such a person who can do this successfully will become a node, and you can have hundreds of such nodes.

One should look at the user interfaces and then design their products and services. With such an approach, multiple users will benefit – like an insurance agency or a lending organisation or industry supply chain actors as well. The idea is to be aware of the bigger picture and create customisable solutions.

Q) So, it is essential to have that user focus; and the user and the entire market has to be big enough for you to sustain your business. But the education level on utilising analytics derived from remote sensing data varies across the industry value chain, and most of the users are unsure of how to trust the results since they aren’t party to the modelling and assumptions that have gone behind it.

The final question is that once we cross this hurdle, what is the usability of these geospatial insights for extracting value for the business? Do you think that the lack of industry standards around the data quality and modelling processes could help address such challenges? Would it help open new markets and allow the users to differentiate between companies’ basis the quality of work, rather than be confused by marketing jargons?

Dr Dadhwal:

A challenge which I faced was when targeting an output which was already being produced by a non-Remote Sensing approach. We spent a decade in arguing and making comparisons, and then there would be turf wars like why should the space guys do forecasting. The argument is still the same, but the actors have changed. Now, these commercial companies and youngsters should not get into these turf wars. So if you find or develop a new market, just move into it and do not wait for the government to establish standards and certifications.

There are other challenges which are in the heart of the system – it can either be related to making an observation, creating a crop model with an additional layer or any other extracted parameter. You can then add the application-specific information, based on the type of user. Unfortunately, many people don’t think that way and consider it more like a pipeline with generic. So, if tomorrow the Sentinel satellite fails, you can replace it with Landsat or an alternate source. Unfortunately, many players have not been able to get this in place in their system design. Several problems arise which could be difficult for users to overcome. The question of acceptance will always be there in the remote sensing industry, and it’s within the acumen of the entrepreneur to overcome them.

This article was first published in The SatSure Newsletter

Add comment